As Philippine banks accelerate the use of passkeys and biometric authentication, a quieter vulnerability is emerging behind the scenes — account recovery.

According to iProov, a digital identity technology provider, the most significant risk facing banks today is no longer how customers log in, but how they regain access when something goes wrong.

As financial institutions tighten onboarding and authentication under new regulatory requirements, attackers are increasingly shifting their focus to recovery processes that have not evolved at the same pace.

“Once you make one part of the journey very strong, criminals stop attacking that and move to whatever is easiest,” said Dominic Forrest, Chief Technology Officer at iProov, in an exclusive interview with FintechNewsPH. “In many cases, that’s account recovery.”

Dominic Forrest, Chief Technology Officer at iProov

For Philippine banks operating in a mobile-first environment, the implications are substantial. Device loss, phone upgrades, SIM swaps, and account resets are common customer scenarios, yet recovery methods are often weaker than the controls used during initial account creation.

Strong logins, weaker recovery

The issue is emerging alongside the implementation of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) Circular No. 1213, which requires banks and other financial institutions to adopt stronger identity verification measures, including biometrics and passkeys, particularly for digital onboarding and high-risk transactions.

The regulation has raised the bar on account creation, making it more difficult for fraudsters to open new accounts using stolen or fabricated identities. However, Forrest said the improvement has also created a new imbalance.

“Banks now know very well who is creating an account,” he said. “The challenge comes later — when a customer changes phones, loses a device, or needs to rebind their account. The methods used at that stage are not always as strong as the original identity verification.”

In practice, this means a bank may require biometric checks to open an account, but rely on SMS one-time passwords (OTPs), call center verification, or device-based credentials when a customer needs to recover access. That mismatch, iProov warns, creates an increasingly attractive entry point for attackers.

Why recovery has become the pressure point

Account recovery presents a unique challenge because it often occurs when a customer no longer has access to the device or credentials originally used to authenticate. While passkeys are more secure than traditional passwords, they are typically tied to a specific device, making recovery necessary when that device is lost or replaced.

“If you want to run a truly digital service, you can’t tell people to go into a bank branch every time a phone stops working,” Forrest said. “The recovery process has to exist, and it has to work remotely.”

Globally, iProov has observed a pattern: as onboarding becomes stronger, criminals shift away from creating fake accounts and toward taking over real ones. Rather than attacking the front door, they target recovery flows that are easier to exploit.

The consequences are often severe for customers. When banks detect suspicious activity, accounts are frequently frozen, leaving legitimate users temporarily unable to access their funds.

“These are real people whose lives are turned on their heads,” Forrest said. “Their accounts are taken over, their fraud markers are triggered, and suddenly they have no access to their money.”

The limits of OTPs and legacy methods

One of the most common recovery tools still used by banks is SMS-based OTPs. Forrest was direct in his assessment of their security.

“OTPs were never designed to be secure,” he said, pointing to structural weaknesses in telecom networks, interception risks, and flawed implementations that allow codes to be reused within time windows.

SIM swap fraud further compounds the problem. By taking control of a victim’s mobile number, attackers can intercept recovery codes without ever breaching the bank’s systems directly. Call center checks, meanwhile, remain vulnerable to social engineering, particularly when criminals already possess partial customer information.

At the heart of the issue, Forrest said, is that many recovery systems authenticate possession of a device or credential rather than the person behind the account.

“The bank account does not belong to the SIM card. It does not belong to the mobile phone,” he said. “It belongs to the human being.”

Biometrics beyond onboarding

iProov argues that biometrics must play a role beyond onboarding and login, particularly during high-risk events such as account recovery, device rebinding, and large-value transactions.

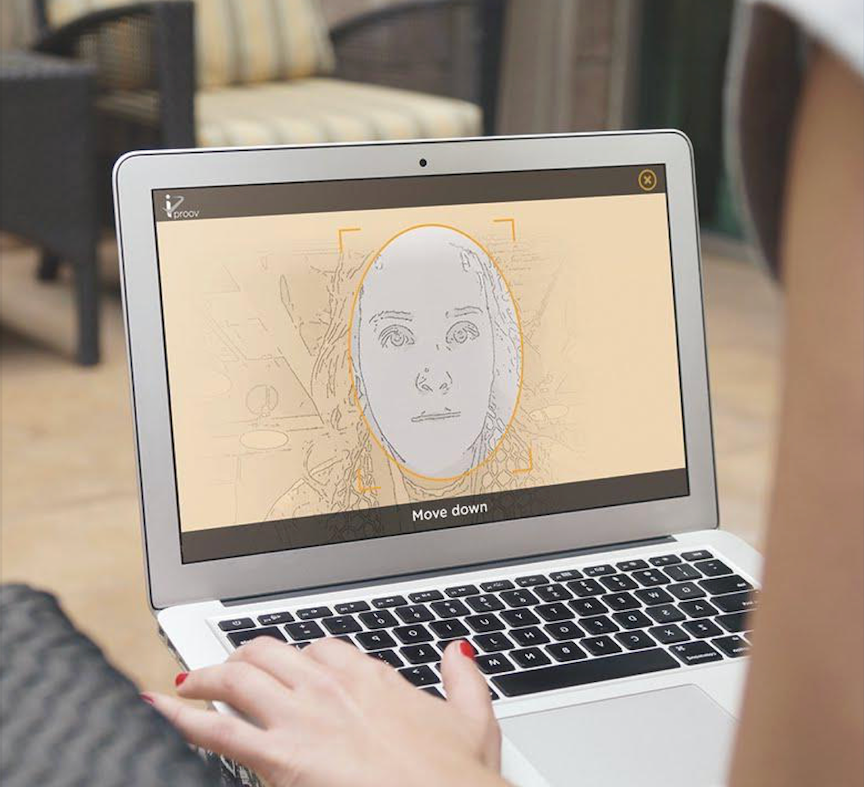

The company focuses on three core checks during remote verification: confirming it is the right person, confirming the person is real and not digitally manipulated, and confirming the authentication is happening in real time.

Advances in generative AI have made this increasingly important. Forrest demonstrated how deepfake tools — now freely available and easy to use — can convincingly impersonate individuals using a single publicly available photo.

“A human eye can no longer tell the difference,” he said, describing how face swaps and synthetic video can bypass traditional visual checks.

A growing risk as 2026 approaches

Forrest said the impact of weak recovery systems is likely to become more visible by 2026, as attackers scale account takeovers and synthetic identity fraud.

In one re-onboarding exercise involving 10,000 accounts at a bank outside the Philippines, Forrest said around 40% of the flagged accounts were found not to be under the control of the legitimate user.

“That’s not a percentage problem — that’s thousands of real people,” he said, emphasizing the personal toll behind the numbers.

The risk, he added, is not limited to banking. As financial institutions strengthen identity controls, attackers may pivot toward other sectors classified as critical national infrastructure, including power grids, telecom networks, and healthcare systems.

“The attack vector is identity,” Forrest said. “If you can compromise that, you can compromise systems far beyond banking.”

What banks can do now

For Philippine banks, the solution is not abandoning passkeys or biometrics, but applying them more strategically across the account lifecycle.

Rather than enforcing uniform authentication for every interaction, Forrest advocates a risk-based approach. Low-risk actions may rely on device-level security, while high-risk events — such as recovery, rebinding, or unusual transfers — should require stronger identity verification tied directly to the individual.

He also urged banks to align with established global identity standards and subject their systems to independent testing and certification.

“This isn’t a one-time fix,” Forrest said. “Identity needs to be something you continuously validate over time.”

As Philippine financial institutions continue to expand digital services and onboard new users, iProov’s warning is clear: without strengthening account recovery, even the most secure logins may not be enough to keep customers safe.